The Great Lakes Storm of 1913 stands as a sobering reminder of nature’s untamed force. Over a century later, the echoes of this monumental tempest resonate through Michigan’s maritime history. This article delves into the storm’s impact, the lives it touched, and the lessons learned in its wake.

Covering the White Hurricane On The Great Lakes 1913

The Largest Marine Catastrophe on the Great Lakes

Much attention has been paid to the sinking of Edmund Fitzgerald on November 10th, 1975. The loss of the largest ship in the 1000-foot Laker fleet and the loss of 29 lives was a horrific event. However, the most savage storm in the history of the Great Lakes swept the inland waters on November 7-12, 1913. The 1913 Great Lakes Storm resulted in the sinking and damage of many ships and hundreds of crewmen and women killed in the icy Great Lakes.

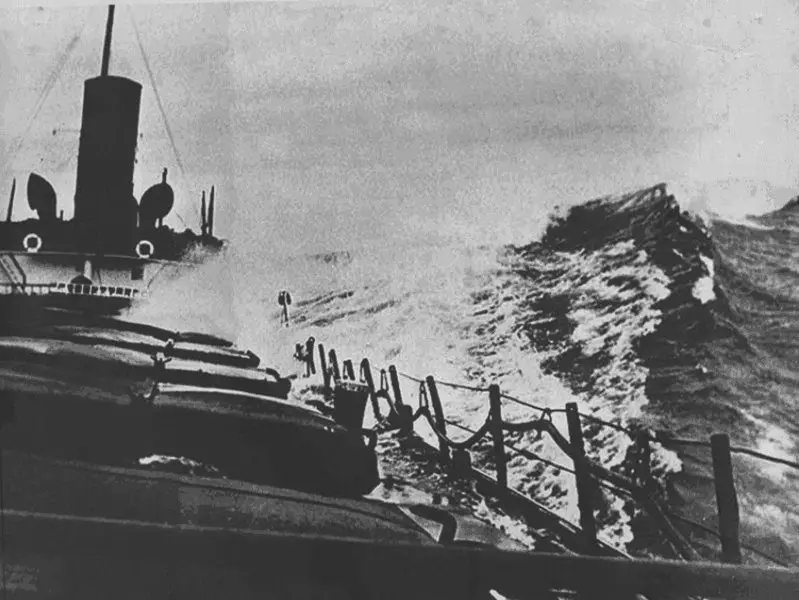

The White Hurricane was formed by two storm fronts’ combined forces colliding with gale-force winds bringing 35-foot monstrous waves and driving snow and ice that doomed anyone caught out on the big lake. The most significant losses in lives and ships occurred on Lake Huron, where 27 were lost or severely damaged. All told, 19 ships lost in the 1913 Great Lakes storm, and a total of 248 souls were lost. Many of the ships that went down were along the Michigan Thumb coastline.

The 1913 storm remains the most devastating natural disaster and worst storms on the Great Lakes.

Early Warnings from the Weather Bureau

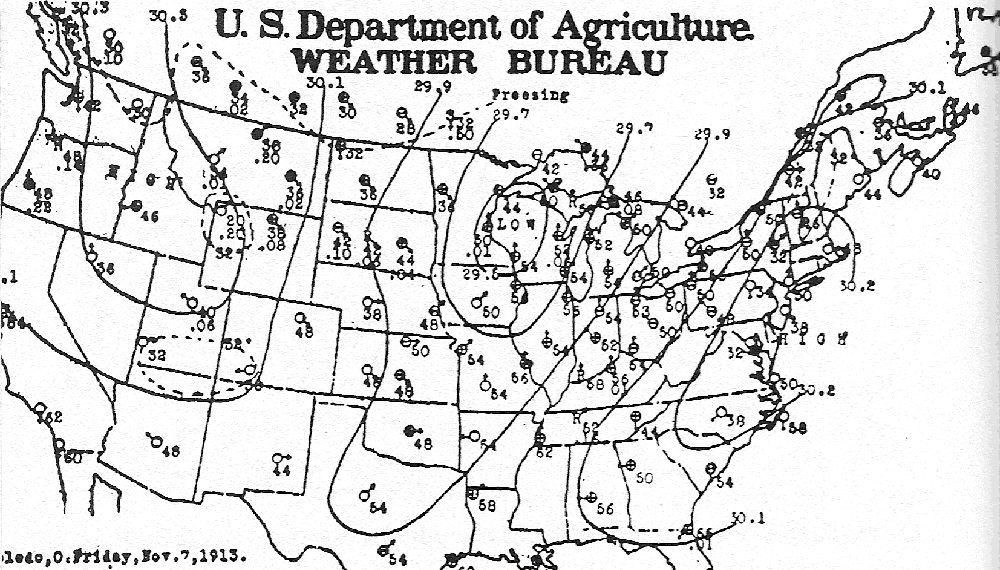

It was a cool Wednesday, November 5th, in Detroit. Temperatures were hovering around 30F, a typical late fall day. The weather forecast in The Detroit News called for “moderate to brisk” winds for the Great Lakes, with occasional rains Thursday night or Friday for the upper lakes (except on southern Lake Huron), and fair to unsettled conditions for the lower lakes.

On Thursday, November 6th, the storm was organized over Minnesota and western Wisconsin. An arctic blast of cold air was starting to creep in on North Dakota. Forecasts across the region predicted high winds and falling temperatures through Saturday.

November 7th – The Great Storm Grows

Friday, the 7th, brought on the start of the storm. The weather service posted a hurricane warning with estimated winds exceeding 70 mph. Lake Superior winds were popping around 50 mph, and snow started over Superior by evening. Thus, the stage was set for the system to slide over the entire Great Lakes region as the storm slid toward Lake Superior’s eastern edge by nightfall.

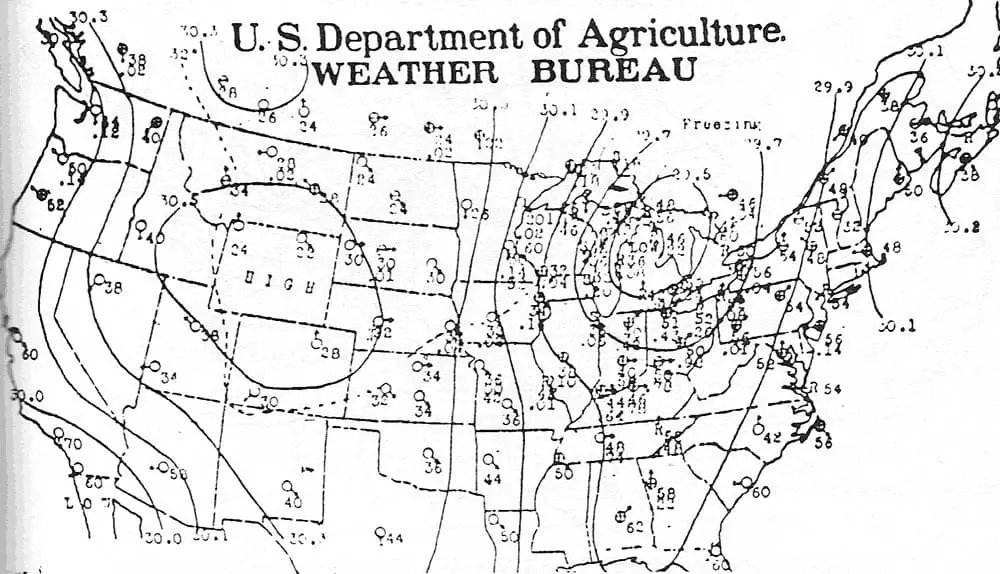

On Saturday, November 8th, 1913, the Weather Bureau reported a severe storm centered over the entire lake region. The forecast was that “the wind will shift to the northwest on Lake Huron sometime this afternoon or early evening and will attain about 50-mile speed on the open lake, especially in the northern half.”

Some noted that on late Saturday, the winds started calming, and the barometer rose a bit. Some captains ignored the storm warning and proceeded up the St. Mary’s River near Sault St. Marie and along the Straits of Detroit between southern Lakes Huron and Erie.

The Massive Storm Hits Lake Huron and Michigan’s Thumb

The storm swept down and fastened its grip on the Thumb area on Sunday afternoon, November 9th. Towards evening, the wind grew in velocity, and streetcars in Port Huron were stopped in their tracks by huge snowdrifts. The lightship, believed to be so securely moored against all storms, was torn away from its fastenings and lifted to the Canadian side, where it was stranded.

Unknown to most was a low-pressure front creeping north in a counter-clockwise motion up from Lake Erie. By early evening Sunday, cities along the southern coast of Lake Erie were being bashed by up to 80 mph winds in Cleveland along with a dramatic drop in barometric pressure.

The First Freighters Are Hit By 1913 Great Lakes Storm

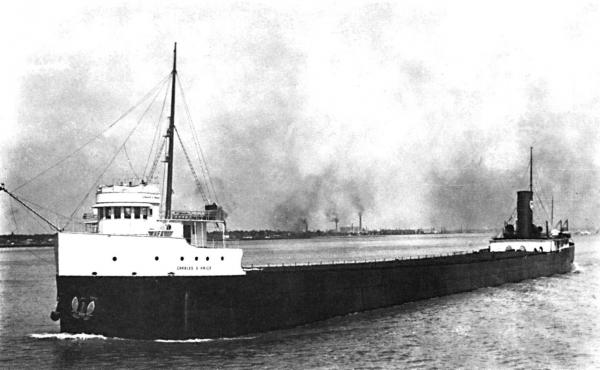

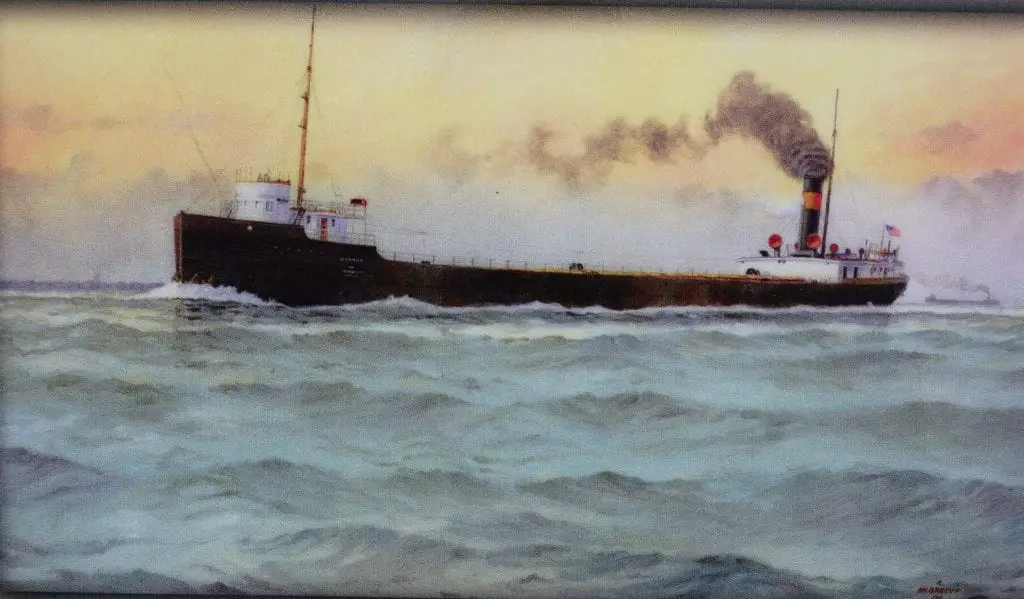

On Lake Huron, seventeen ships were on the water. The giant freighters were tossed about by northeast winds blowing from seventy-five to eighty miles an hour. One of these steamers was “Charles S. Price,” which received more news coverage than any other ship. On Saturday morning, the Price, laden with soft coal, left Ashtabula, Ohio.

When the freighter passed the town of St. Clair before dawn on Sunday morning, November 9, Second Mate Howard Mackley gave a short blast of the whistle as a signal to his young bride that he was passing, and in reply, she turned on an upstairs light in their home. By dawn, the Price was making its way up to Lake Huron.

About noon Sunday, the Price was seen north of Harbor Beach by Capt. A. C. May of the Steamer H. B. Hawgood. Then, on Monday afternoon, a giant steel freighter was seen floating upside down in the lake about eight miles north and east of Lake Huron’s mouth. Many people were anxious to learn the steamer’s name, although it was generally believed the Regina.

Attempts to Identify the Doomed Ship

On Wednesday morning, an attempt was made to find out the vessel; however, the diver did not make his descent due to the high seas. Lake Huron kept its awful secret for almost a week. It was not until Saturday morning, November 15th, that William H. Baker, a diver from Detroit, solved the mystery. He read the steamer’s name twice when he went down, and the letters spelled out Charles S. Price.

The forward part of the ship’s bottom was buoyed up by air held in her when she turned turtle, but two streams of bubbles were coming out of the bow, which meant that she would settle gradually. On Monday morning, November 17th, the Price disappeared from view.

The Charles S Price was built in 1910 at Lorain, Ohio. A steel bulk freighter, measuring 524 x 54 by Mahoning Steamship Co. 6,322 tons gross. The Price was officially listed as lost in Lake Huron, approximately 8 miles north of Port Huron, with all hands, 27 men, and one woman. Capt. W. M Black, Chief Eng. John Groundwader. Its cargo was listed as coal. (2)

The Wexford Grounds in Canada

Two companies attempted salvage operations on the Price three years later. Both abandoned the attempt. While the mystery of the ship’s identity floating upside down was solved, another mystery remains unsolved. How did it happen that several bodies found along the Canadian shore were identified as from the Price’s crew, but they were wearing life belts bearing Regina?

The White Hurricane

Ships Lost on Lake Huron During the Freshwater Fury

Other ships that went down in Lake Huron during the massive storm were:

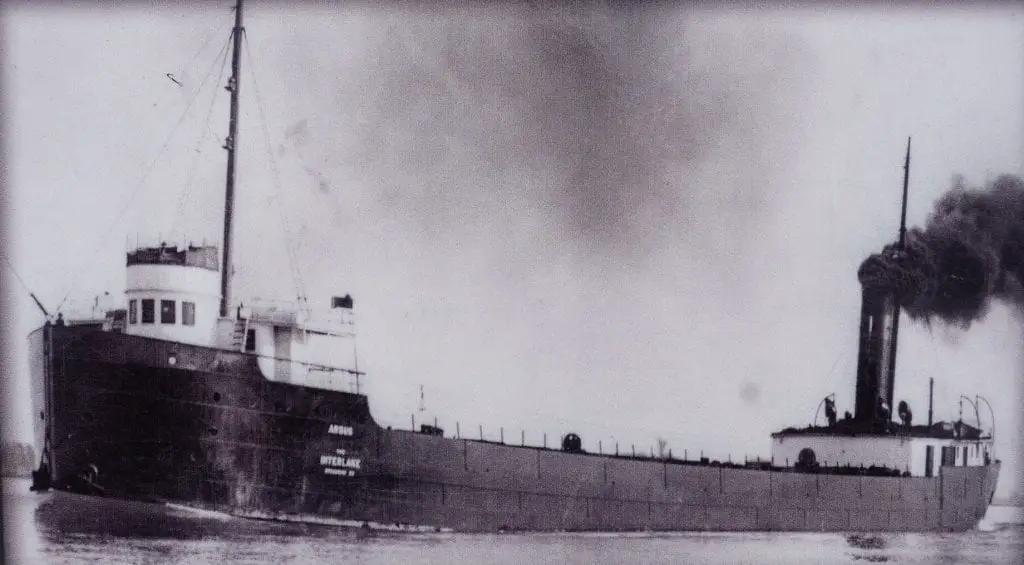

The Argus

The SS Argus sank off of Pointe Aux Barques early evening of November 9th with 28 crew onboard. Reports were that she broke in two with her hold full of coal. The wreck of the 436 foot Argus was found near Kincardine, Ontario, in 1972. Argus looks to have been refitted in 1913 in Lorain, Ohio. Her former name was Lewis Woodruff. A fleet mate of Hydrus who also sank in the storm, she was owned by Pickens, Mather & Co. of Cleveland.

James Carruthers

Thought to have sunk near Grand Bend, Ontario, at midnight on November 10th, with 22 lives lost. This ship has yet to be found. The James Carruthers was one of the Lakes’ newest vessels; the vessel was heavy and built with extra steel to ensure seaworthiness. Unfortunately, even these state-of-the-art improvements to shipbuilding couldn’t save the ship from the storm’s rath.

The Regina

Built in Scotland and crossed the Atlantic to Regina’s homeport in Montreal, Canada. She is described as a floating general store in that her manifests typically denote her carrying paint, kitchen utensils, hardware, cloth, and food supplies. On this fateful day, she was steaming north from Port Huron, heavy with a sewer pipe.

Captain Edward McConkey was running the Regina southbound along the shore near Lexington. The crew was running blind as the wheelhouse was caked with thick ice. As the storm pushed her into the coast, the ship hit bottom. Tearing a hole through the hull, the crew anchored and tried to run the pumps. It was hopeless. The captain stayed on board while he ordered the crew to abandon the ship.

People on shore said they could hear the captain blow the whistle until around midnight. According to local divers, Regina was thought to be capsized late on November 9th, but the wreck is still in one piece. She rests on the bottom three miles off the eastern shore near Port Sanilac with 20 lost.

Hydrus

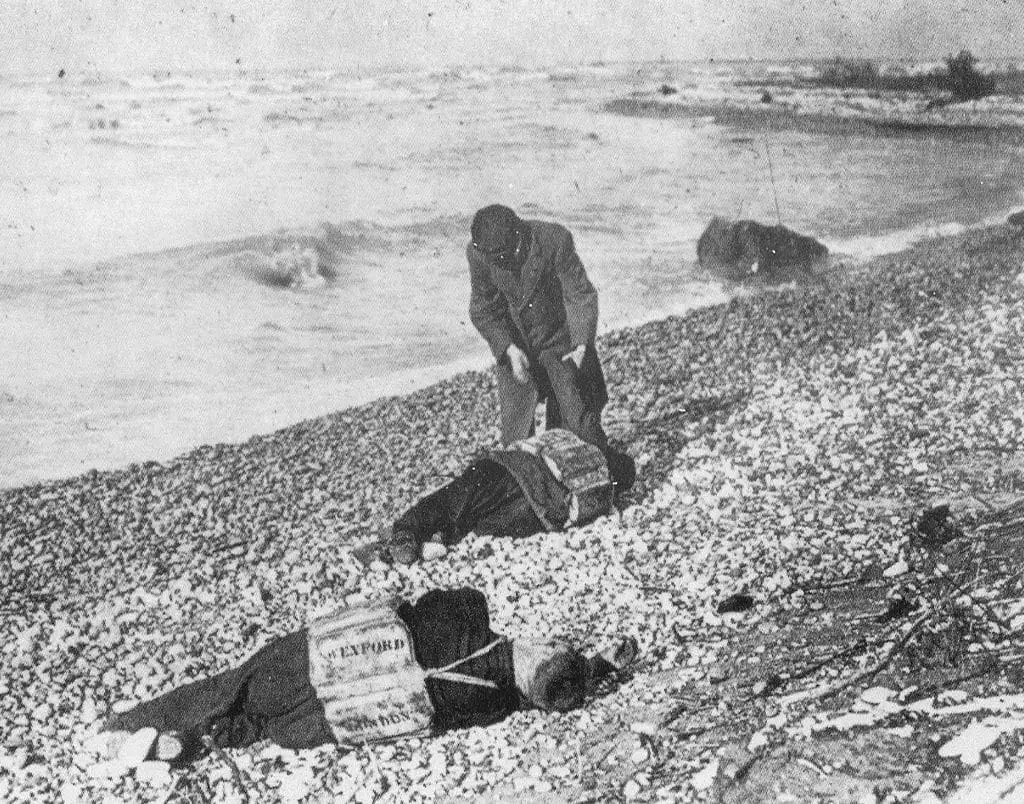

The Hydrus was thought to be forever lost. The 436-foot steamer was heading south on November 9th with a load of iron ore. Initial estimates put her at the outer mouth of Saginaw Bay near Rogers City when she sank. But she was found in 2013 by divers near Goderich, Ontario. Five of her crew were found frozen in their lifeboat when it washed up onshore.

John A. McGean

The 432-foot freighter was running north after taking on 6,000 tons of soft coal at Sandusky. The John A. McGean sank near Pointe Aux Barques and Port Hope on November 9th with 28 onboard.

Isaac M. Scott

Isaac M. Scott foundered and sunk near Alpena on November 9th with 28 onboard. Before sinking, it’s thought that the Isaac M. Scott capsized in the Lake Huron waves.

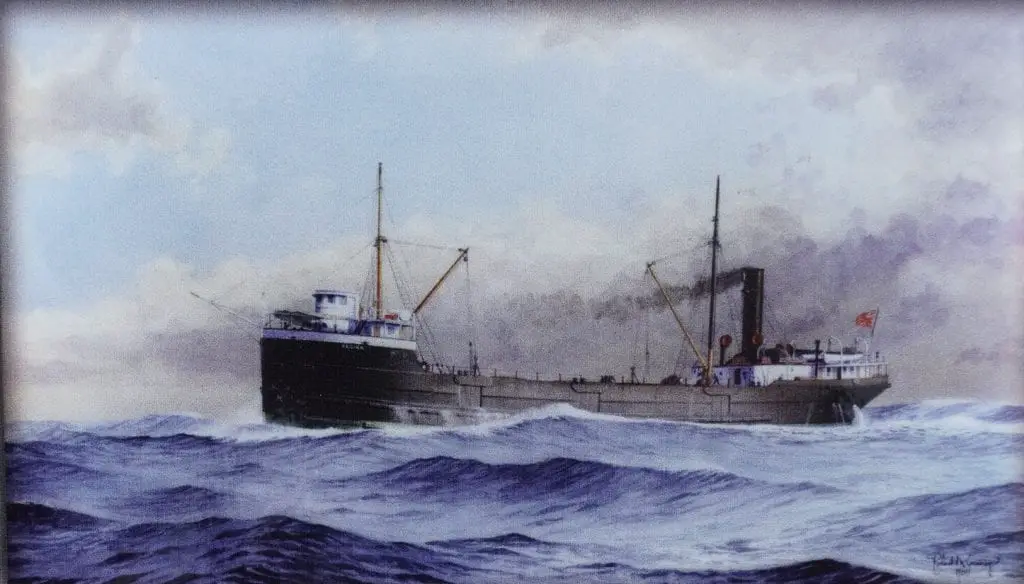

Wexford

The Wexford went down near Goderich, Ontario, with 20 on broad. The ship went down on the southeastern side of Lake Huron.

The Wexford was heading south from Fort William/Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay) with a grain cargo and was scheduled to dock in Goderich. There are stories about Goderich residents who thought they heard the ship’s whistle. However, the vessel was assumed to be making a futile attempt to signal for assistance because it could not discover or maneuver into the harbor under horrific circumstances.

Wexford’s captain was Collingwood’s newly appointed Frank Bruce Cameron. He was just 26 years old, but he came from a family of seamen, so he was an experienced and capable sailor for his age. Unfortunately, this was also his first and last voyage as a ship’s master, as he was the most junior captain to perish in the 1913 storm.

In all, eight ships and 189 lives were lost on Lake Huron. For days after 1913, Great Lakes storm relatives of the men who lost their lives patrolled the shore in the hope of finding their bodies.

After the Great 1913 Storm

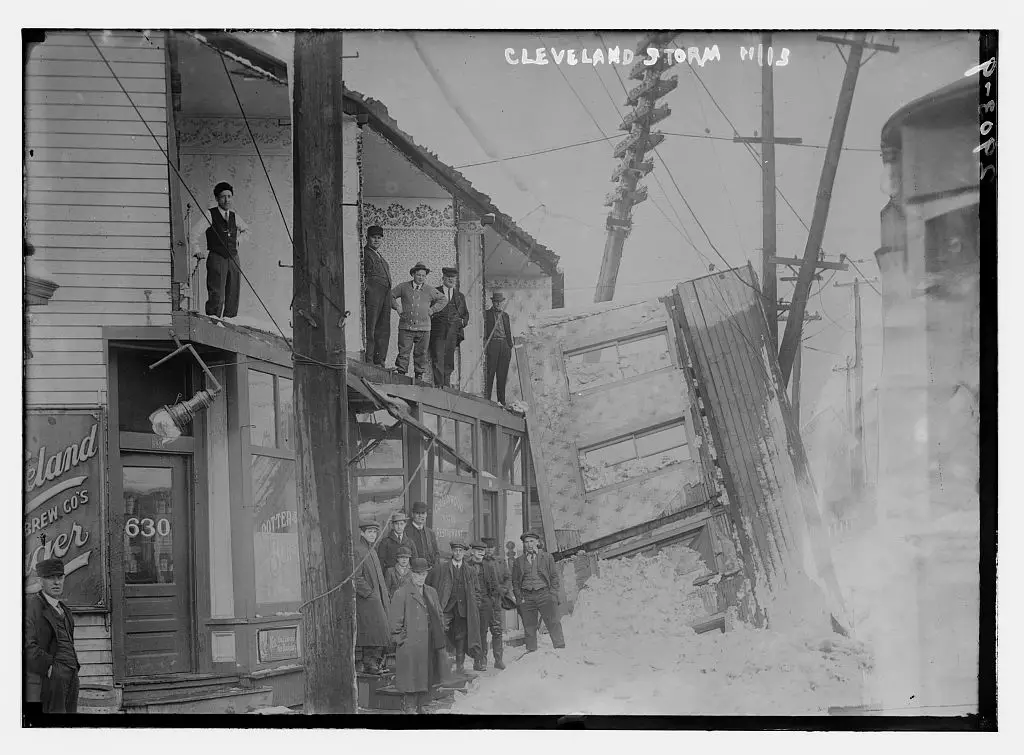

Cities from Port Huron South received the brunt of the lake-effect snow. Cleveland experienced 17.4 inches of snow falling in 24 hours, with a three-day total of 22.2 inches. The snowstorm paralyzed the city, with nearly all businesses, factories, and schools closed on November 10th.

Streetcars and trains rolled at a crawl, and roads were impassable. Cleveland suffered extensive power, telephone, and telegraph outages, and lines snapped with the weight of the snow. Snow drifts from 4 to 5 feet were reported from Port Huron, south to Cleveland, Ohio.

Life-Saving Station at Pointe Aux Barques Smashed

By mid-afternoon midday Sunday, the snow was driving horizontal from the northeast toward the shore at Pointe aux Barques. The snow was so thick and so heavily driven by the wind that ships out on the lake could not see the rays of the lighthouse.

The Life Saving Station, located close to the beach, was hammered by waves and hurricane-strength winds for 16 hours. After the storm, the station was a pile of debris.

The Grounding of the S.S. M.W. Hanna At Port Austin Light

Other Ships Sunk in the Great Lakes

On Lake Erie, the lightship #82 Buffalo vanished to the depths on the evening of November 10th. The only indication that the ship was in trouble occurred the next day that a lifebuoy bearing the lightship’s name and other small wreckage items had been picked up on the beach inside Buffalo Breakwater. Six lives were lost in the Freshwater Fury storm. The Buffalo was salvaged several years later and served in various locations around the Great Lakes until 1937.

News Coverage of the 1913 Great Lakes Storm

News of the disaster trickled in over the next several days. The biggest story was pictures and descriptions of a capsized ship discovered drifting north of Port Huron. The story of the mystery ship lasted for days until a diver was dispatched and identified the hull as the Price.

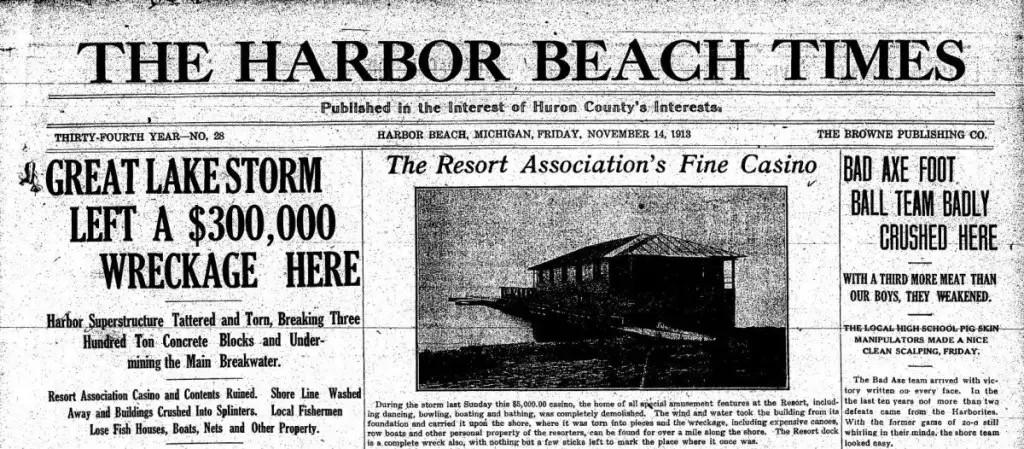

All along the eastern shoreline of Michigan’s Thumb were stories of devastation. The huge weatherproof breakwall of the harbor was undermined. Scores of fishermen had boats, fish houses, and ice storage buildings destroyed. Docs and piers that had been in service for generations were gone. One story tells that many ships in the harbor were blasting their whistles and horns for hours on end. There was no way to stop it. Ice had covered the whistle lines, resulting in a continuous performance throughout the night.

The devastation didn’t limit itself to the coast. In Harbor Beach, the hardware store had its plate glass window blown in, and over four feet of snow covered the showroom. The same fate occurred at the town’s creamery. Western Union telegraph lines all iced up and were downed. This effectively cut off communications.

1913 Great Lakes Storm Research and Simulations

In simulations of NOAA’s storm, the estimated wind gusts exceeded “hurricane-force” (greater than 74 mph) during extended periods over Lakes Huron, Erie, eastern Superior, and Lake Michigan. Huron: 10 hours, Superior: 20 hours, Michigan: 13 hours, Erie: 16 hours.

Waves likely doubled in height from the afternoon to the evening of November 9th. Waves were especially deadly around the mouth of Saginaw Bay, whereas several large ships encountered incredible winds and Great Lakes storm waves. Thus, from 6 pm to Midnight on November 9th is considered the most lethal in Great Lakes history. Nine large vessels and over 200 crew and passengers were lost. Eight ships and 187 lives were lost over southern Lake Huron in the Freshwater Fury of the 1913 Great Lakes Storm.

Video of 1913 Great Storm

The Storm is Remembered Today

In Port Huron, a city located at the southern end of Lake Huron, at the easternmost point of land in Michigan, there stands a small monument on the waterfront that tells the story of the “Great Storm of 1913” that hit the American Great Lakes. This storm, also known as the “White Hurricane,” brought hurricane-force winds that overwhelmed four out of the five Great Lakes. It remains the deadliest and most destructive Great Lakes storms ever recorded in the history of the lakes, as of 2019.

The White Hurricane 1913 FAQs

What was the Great Lakes Storm of 1913?

How many ships were lost in the Great Lakes Storm?

What changes occurred after the 1913 storm?

Related Historical Stories About the Great Lakes

Sources of the 1913 Great Lakes Storm

- Information taken from Telescope Magazine, November 1963, pages 247-253.

- Based on a thesis written by Robert A. Dongler, Michigan State University, East Lansing.

- The New History of Michigan’s Thumb by Gerald Schultz, 1969 pp 105-107

- Pointe Aux Barques Lighthouse and Museum

- A weather map from the Weather Bureau’s Toledo observer and published in the Toledo Blade on Nov. 1913

- Catastrophic Disaster in the Maritime Archaeological Record: Chasing the Great Storm of 1913 By Sara Christine Kerfoot, April 2015

- NOAA.gov “Centennial Anniversary Storm of 1913”

- The “White Hurricane” Storm of November 1913, A Numerical Model Retrospective” presentation

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes, Lightship No. 82, sunk, 10 Nov 1913

- The Great Lakes “White Hurricane” of 1913 – St. Joseph Historical Society

Like this Story? Share to Pinterest