Recently I read a book written in the late 1800s by Andrew Blackbird. Blackbird was an Ottawa tribal leader and historian. His book, History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan, strove to correct some historical errors regarding Michigan Indian tribes. The tales and descriptions of life in the early 1800s are worth the read. Some of Blackbird’s top corrections are inciteful. Here are the top five.

What We Will Cover

#1 We Pronounce “Pontiac” All Wrong

Living in Michigan, I was taught that Chief Pontiac was a Native American war leader who masterminded and organized an uprising and siege of the British forts in Detroit and Mackinac in 1763. However, I was taught to say his name all wrong. It is spelled Pontiac, but in Ojibwe (or Chippewa), his real name is pronounced: “Bwon-diac“.

#2 Michigan Indian Tribes Didn’t Have “Cities”

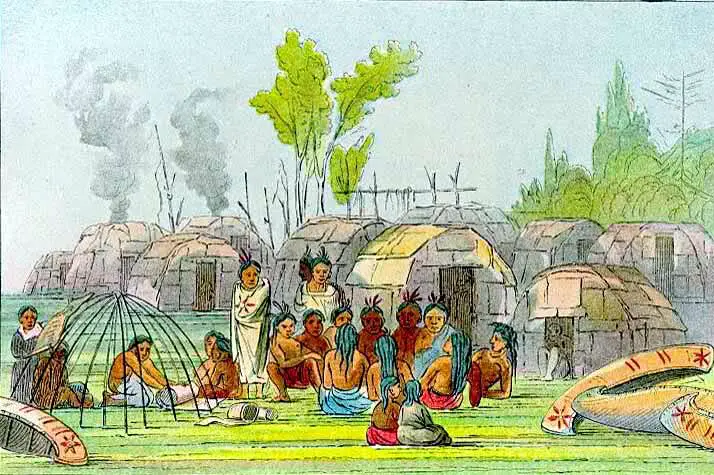

I was taught in school that the Michigan Indian tribes were primarily nomadic hunters and gathers. That they would set up their wigwams only for months at a time and then move on. This is only partially true. It turned out that both the Ottawa and Chippewa tribes had huge settlements that spanned miles.

The whole coast near today’s Harbor Springs was called Waw-gaw-naw-ke-zee. It was a huge continuous village some fifteen or sixteen miles long and extending from what is now called Cross Village south along the Lake Michigan shore to Harbor Springs. It was said that the reason that we see no old-growth trees standing along this coast (also known as Arbor Croche) for a mile inland is that the trees were entirely cleared away to make lodges for this famous long village. Just about the entire Ottawa population was wiped out by smallpox which the village never fully recovered.

#3 The Names Mackinac and Michilimackinac mean “large turtle” in the Ottawa and Chippewa language

We were taught that the name of the beloved island on the straits of Mackinac was derived from the Michigan Indian Tribes of the Ottawa and Chippewa word meaning “large turtle.” Mackinac Island looks like a turtle from the water so as a kid it’s believable. However, this is not the case.

According to Ottawa’s oral tradition, the island’s name was derived from the tribe of people named “Mishi-ne-macki-naw-go,” who lived on nearby islands on North Lake Huron in the 1300s. This tribe was annihilated at Manitoulin Island by the Iroquois of New York. However, two members of this ancient tribe escaped fled to Mackinac and hid in the natural caves on the island. The Ottawa took the two who survived and lived out their days. The Ottawa and Chippewas named this little island “Mi-shi-ne-macki-nong” to memorialize the extinct tribe with the Indian noun “Michinemackinawgo.” They contend this is where the name Michilimackinac is originated.

#4 Chief Tecumseh was killed by an American soldier named Johnson

We were taught that this war chief was killed during the war of 1812. Currier and Ives’ lithograph shows the chief shot by Col. R.M. Johnson using a pistol to kill Tecumseh at the battle of the Thames in Ontario. However, his true demise was much wilder.

During his last battle, Tecumseh ordered his warriors to rally and fight the Americans again. A musket ball went into Tecumseh’s leg, breaking a bone so he could no longer stand. Sitting on the ground, he told his warriors to retreat and save themselves.

The Ottawa accounts for the chief’s last moments as follows. Tecumseh said, “One of my legs is shot off! But leave me one or two guns loaded; I am going to have a last shot. Be quick and go!” That was the last word spoken by Tecumseh. As the tribe looked back, they saw American soldiers thick as a swarm of bees around where Tecumseh was sitting on the ground with his broken leg, and so they did not see him anymore; and. Therefore, we always believe that the Indians or Americans not know who made the fatal shot on Tecumseh’s leg, or what the soldiers did with him when they came up to him as he was sitting on the ground.

#5 The Assassination of Indian Priest William Maccatebinessi In the Vatican

This little part of history was never taught. Still, it’s a fascinating glimpse of the struggle of the Native Americans as the various treaties slowly chipped away at the tribal lands in Michigan.

William Maccatebinessi was a boy of one of the Michigan Indian tribes who attended the Protestant Mission School on Mackinac Island. Soon he commanded the English language and acted as an interpreter among the Indian camps on the island. When he was about 16, William was taken by Bishop Rese with his little sister to Cincinnati, Ohio, to continue his education. In January 1831, he taught the Famous missionary Fredrick Baraga the Ottawa language.

He traveled to Rome, Italy, to study for the priesthood. He developed into a very eloquent and powerful orator, was considered an auspicious man by the Rome elite, and received great attention from the noble families because of his wisdom and talent and his being a Native American.

While he was in Rome, the United States government proposed to buy out the Michigan Indian Tribes. William wrote to his people at Arbor Croche and Little Traverse and advised them not to sell out nor make any contract with the United States Government but to hold on until he could return to America. William wanted to provide counsel and aid them in making out the contract or treaty with the United States. He told them never to give up, not even if they should be threatened with annihilation or driven away at the bayonet point from their native soil.

William told his cousin that if he ever set his foot again on American soil, his people, the Ottawas, and Chippewas of Michigan, should always remain where they were. The United States would never be able to compel them to go west of the Mississippi, for he knew how to prevent them from being driven off from their native land. He also told his cousin that he would at once start for America and go right straight to Washington as soon as he was ordained and relieved from Rome. William would seek to see the President of the United States, to hold a conference with him on his people and their lands.

On June 24th, 1833, the night before he was to be ordinated as a priest in Rome, his brother asserts William was assassinated. His papers and correspondence, which were assumed to offer details on negotiating with the United States, were shipped to Detroit but mysteriously lost in transit.

It was never discovered who murdered the powerful Indian priest. A letter was sent to Bishop Rese from Rome indicating that the young man may have died from an aneurysm. Still, it was assumed that there was a conspiracy to get rid of William before making his way to see the United States president and provide counsel for negotiating for the Michigan Indian tribes.

#6 Great Lakes Tribes Did, And Still Have A Large, Interdependent Relationship

Little was taught of the extensive trade, family, and relationship building that went on between the various tribes of the Great Lakes. We thought each tribe kept to itself and had wars over territory and hunting grounds. Some of the thoughts undoubtedly came from the Western shows common on TV in the 1960s.

I was surprised to learn much later at Michigan State University about the Three Fires Confederacy: The Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi tribes formed a political and spiritual alliance called the Council of Three Fires. The purpose of the confederacy was to maintain peace, provide mutual defense, and promote cooperation among the tribes. Each tribe had its own roles and responsibilities, with the Ojibwe as the “Keepers of the Faith,” the Odawa as the “Keepers of the Trade,” and the Potawatomi as the “Keepers of the Fire.”

#7 Critical Role Of Women In Tribal Formation and Selection of Leadership

As kids, the role of Native American women wasn’t even mentioned. We saw them as Indian versions of TV mom Joan Clever in Leave It To Beaver. I later understood that women in many Michigan Indian tribes held significant roles in their communities. They were responsible for farming, gathering, preparing food, crafting, and maintaining households. Women were also involved in decision-making processes and held positions of power and respect. Clan mothers, for example, were responsible for selecting and advising tribal chiefs.

#8 The Significance Of Dream Catchers

Dream catchers are a well-known symbol in Native American culture and originated from the Ojibwe tribe. They were traditionally made using a hoop, sinew or string, and sometimes feathers or beads. The dream catcher was believed to protect people, especially children, from bad dreams and evil spirits. Good dreams would pass through the center hole and slide down the feathers to the sleeper, while bad dreams would be caught in the web and disappear at the first light of day.

#9 The Story Of The Petoskey Stone

The Petoskey stone is a type of fossilized coral found in the region around Lake Michigan, particularly in the area surrounding the city of Petoskey. It is significant to the Odawa tribe, who believe that the stones represent the sun’s rays and their ancestors’ tears. Today, the Petoskey stone is Michigan’s state stone.

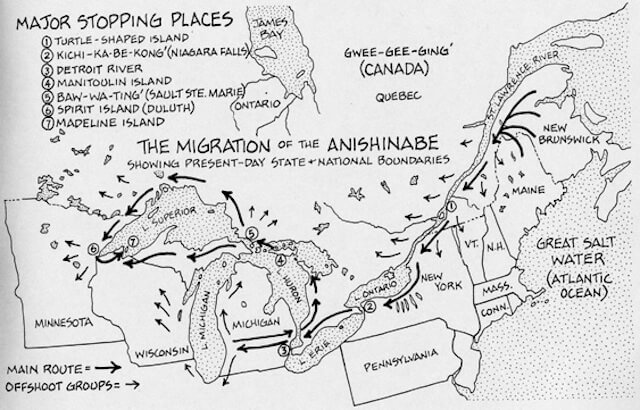

#10 The Anishinaabe Migration Story

We were never taught about the migrations of tribes through various parts of the country. It was assumed that the tribes had inhabited the Great Lakes area for millennia.

According to the Anishinaabe people (which include the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi), their ancestors were instructed by the Creator to follow a prophetic vision to migrate westward from the Atlantic coast. The journey led them to the Great Lakes region, where they were to find the place where food grows on water. This food is believed to be wild rice, a staple of the Anishinaabe diet.

Video: Migration Story of the Anishinaabek

Notes on Keeping the Assertion that William Maccatebinessi was Murdered

Some feel that keeping Andrew Blackbird’s assertion that his brother was murdered is somehow “sensationalist” and “not history” may be overplaying their point of view. It’s worth reviewing a few pieces of information and placing it within context.

- Over 54 years transpired between William Maccstebinessi’s death in 1833 and the publication of History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan in 1887. That’s a long time. It means that Blackbird never was satisfied with the Vatican’s explanation for settling how William died.

- William’s cousin and fellow tribe member, Augustin Hamelin, was also at the Vatican and was on hand to see the body and was in William’s room. According to Blackbird, Hamelin was the first to think his cousin had been assassinated. “When Hamlin, his cousin, heard of it, he too rushed to the room, and after his cousin’s body was taken out, wrapped up in a cloth, he went in and sat at once enough to tell him that it was the work of the assassin.”

- Maccstebinessi was to have been the first aboriginal palate to be ordained a priest. It would have been a scandal and an embarrassment to acknowledge the murder of this celebrity priest in the Holy See. The letter the church sent to Bishop Rese the following July indicating that William had a health issue before his arrival that the Vatican is potentially a reasonable explanation. But it seems too coincidental.

- Williams’s views toward the treaties seem to be well-socialized, and given he was prepared to go directly to the President as a newly ordained priest, it would have been unwelcome news.

Sources For Indian Tribes In Michigan

- FISSION, MAINTENANCE, AND INTERACTION IN AN ANISHINABE COMMUNITY ON KEWEENAW BAY, MICHIGAN, 1832-1881. By Walter Randolph Adams, A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Anthropology, 1988

- Andrew Blackbird’s History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan (1887)

Related Reading Michigan Indian Tribes